Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding

Five less know facts about breastfeeding

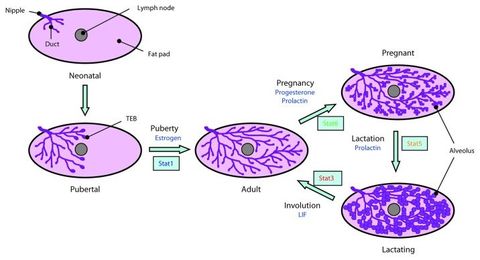

1) Involution

Whether a woman breastfeeds her child for 2 weeks or two years, after her nursing relationship is over, her breasts will - shrink! Yes, it is called mammary gland involution.

Basically, the mammary tissue returns to a size similar to that it had before pregnancy, or even less, while the skin around it stays as large as it was at peak of lactation, resulting in what we today consider unaesthetic hanging breasts. Aside from an aesthetic issue, though, involution can have consequences for breast cancer risk, as explicated in the following article by Silanikove, published in Life Sciences:

In most mammals under natural conditions weaning is gradual. Weaning occurs after the mammary gland naturally produces much less milk than it did at peak and established lactation. Involution occurs following the cessation of milk evacuation from the mammary glands. The abrupt termination of the evacuation of milk from the mammary gland at peak and established lactation induces abrupt involution. Evidence on mice has shown that during abrupt involution, mammary gland utilizes some of the same tissue remodeling programs that are activated during wound healing. These results led to the proposition of the "involution hypothesis". According to the involution hypothesis, involution is associated with increased risk for developing breast cancer. However, the involution hypothesis is challenged by the metabolic and immunological events that characterize the involution process that follows gradual weaning. It has been shown that gradual weaning is associated with pre-adaption to the forthcoming break between dam and offspring and is followed by an orderly reprogramming of the mammary gland tissue. As discussed herein, such response may actually protect the mammary glands against the development of breast cancer and thus, may explain the protective effect of extended breastfeeding. On the other hand, the termination of breastfeeding during the first 6 months of lactation is likely associated with an abrupt involution and thus with an increased risk for developing breast cancer. Review of the literature on the epidemiology of breast cancer principally supports those conclusions.

What can be advised based on the above research, therefore, is not to go "cold turkey" when weaning, but to do so gradually and preferably after 6 months. Moreover, weaning abruptly can also increase the risk of mastitis.

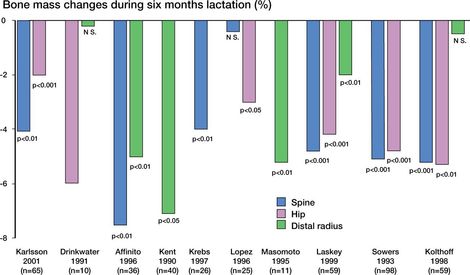

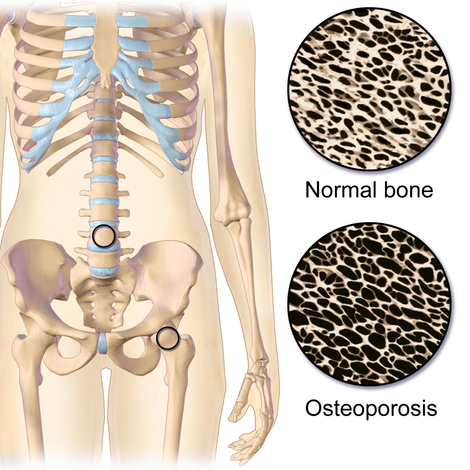

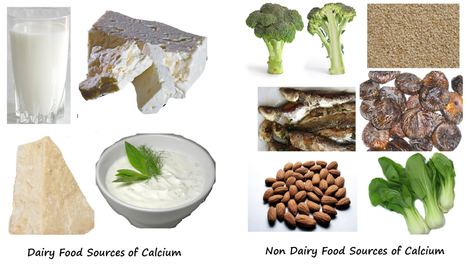

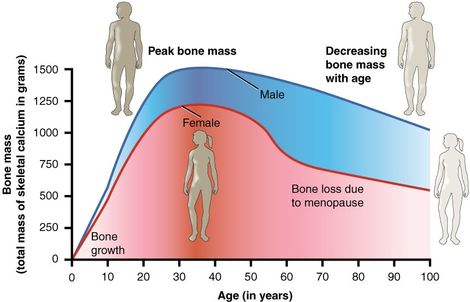

2) Calcium content of the mother's bones

Many mothers lament "loosing their teeth to breastfeeding". Given how rich in calcium milk is, is it any wonder then to think that the mother's reserves get depleted during pregnancy and lactation? Well, no. However, we also know the claim that breastfeeding is good for the mother's health. So what happens then? Well, during pregnancy and the early breastfeeding period, the mother's bones do decrease in density, becoming more porous. Once the breastfeeding is over, though, the bone stores of calcium replenish and some researchers reported that they become even denser than before! It is therefore a myth that breastfeeding increases the risk of osteoporosis and bone fracture.

This is what Kalkwarf and Specker say in their 2002 article Bone mineral changes during pregnancy and lactation:

Significant calcium transfer from the mother to the fetus and infant occurs during pregnancy and lactation, theoretically placing the mother at an increased risk for osteoporosis later in life. During pregnancy, intestinal calcium absorption increases to meet much of the fetal calcium needs. Maternal bone loss also may occur in the last months of pregnancy, a time when the fetal skeleton is rapidly mineralizing. The calcium needed for breast milk production is met through renal calcium conservation and, to a greater extent, by mobilization of calcium from the maternal skeleton. Women experience a transient loss of approx 3–7% of their bone density during lactation, which is rapidly regained after weaning. The rate and extent of recovery are influenced by the duration of lactation and postpartum amenorrhea and differ by skeletal site. Additional calcium intake does not prevent bone loss during lactation or enhance the recovery after weaning. The recovery of bone is complete for most women and occurs even with shortly spaced pregnancies. Epidemiologic studies have found that pregnancy and lactation are not associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures.

In their 2005 review Maternity and bone mineral density, Karlsson et al. write:

Alderman et al., including 355 post-menopausal women with a fracture and 562 matched women with no history of fracture, reported that the incidence of hip and forearm fractures was no higher in women who had given birth to four or more children than in women who had not given birth. Also, women who had breast fed for more than 2 years did not have a higher fracture risk than women who had never breast fed. [...] Thus, to summarize, half of the studies suggest that there is no association between parity and fractures, while the other half imply that a history of one or several pregnancies is associated with a reduced risk of fracture. Virtually no study has suggested an association between lactation and fracture risk. It appears that having many children leads to a situation that, if anything, leads to not only a higher BMD, but also a reduced fracture risk. [...] Women with several pregnancies and long total duration of lactation have no different or lower fracture incidence that their peers with no or few children. The current data do not support that a pregnancy or a period of lactation can be regarded as risk factors for future osteoporosis and fragility fractures.

To conclude, the 2012 article Lactation is associated with greater maternal bone size and bone strength later in life

by Wiklund et al. states:

Summary

The association between lactation and bone size and strength was studied in 145 women 16 to 20 years after their last parturition. Longer cumulative duration of lactation was associated with larger bone size and strength later in life.

The association between lactation and bone size and strength was studied in 145 women 16 to 20 years after their last parturition. Longer cumulative duration of lactation was associated with larger bone size and strength later in life.

Introduction

Pregnancy and lactation have no permanent negative effect on maternal bone mineral density but may positively affect bone structure in the long term. We hypothesized that long lactation promotes periosteal bone apposition and hence increasing maternal bone strength.

Pregnancy and lactation have no permanent negative effect on maternal bone mineral density but may positively affect bone structure in the long term. We hypothesized that long lactation promotes periosteal bone apposition and hence increasing maternal bone strength.

Results

Sixteen to 20 years after the last parturition, women who had breastfed in total more than 33 months in their life, regardless of the number of children, had greater bone strength estimates of the hip (HSI = 1.92 vs. 1.61) and the tibia (TBSI = 5,507 vs. 4,705) owing to their greater bone size than mothers who had breastfed less than 12 months (p < 0.05 for all). The differences in bone strength estimates were independent of body height and weight, menopause status, use of hormone replacement therapy, and present leisure time physical activity level.

Sixteen to 20 years after the last parturition, women who had breastfed in total more than 33 months in their life, regardless of the number of children, had greater bone strength estimates of the hip (HSI = 1.92 vs. 1.61) and the tibia (TBSI = 5,507 vs. 4,705) owing to their greater bone size than mothers who had breastfed less than 12 months (p < 0.05 for all). The differences in bone strength estimates were independent of body height and weight, menopause status, use of hormone replacement therapy, and present leisure time physical activity level.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding is beneficial to maternal bone strength in the long run.

Breastfeeding is beneficial to maternal bone strength in the long run.

© 2024

All Rights Reserved | Empowering Parenting